Global Marketing Monitor: Weekly Market Trends (November 06, 2021)

- POV’s

- November 6, 2021

- Brian Wieser

WHAT YOU’LL READ ABOUT THIS WEEK:

We review the growth of the consumer goods industry during the third quarter in the face of supply chain issues, along with the related impact (or lack of impact) on advertising. While looking at the economics of supply and demand in media we also assess similar principles as they relate to hate speech on social media.

—

Pandemic-related supply chain issues including transportation bottlenecks and production challenges in an environment featuring heightened demand for semiconductors among other inputs continue as an important topic in the minds of advertising industry observers. There are clearly sectors of the economy that are affected heavily by these issues, but as we have pointed out previously, read-throughs for media companies are often dramatically overstated.

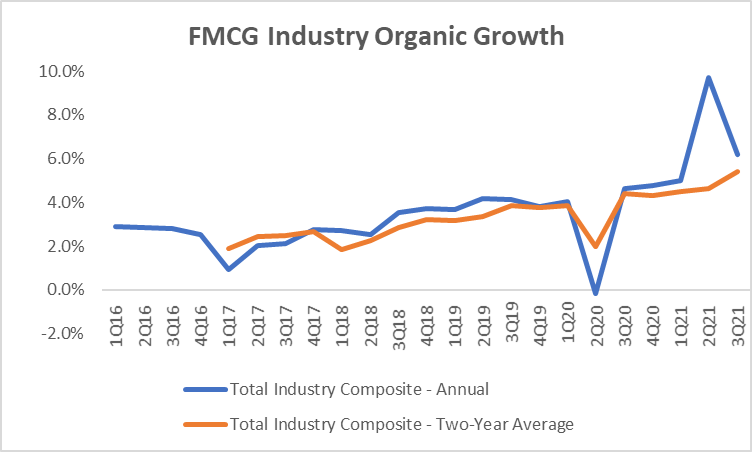

Looking at one category that is seemingly affected by the aforementioned conditions, much of the fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) industry has now reported their third-quarter results, providing a tangible window into the trends those companies are experiencing. Our composite for the sector, which reflects approximately $500 billion in annual revenue, shows a global industry that is collectively in rude health, at least on the top-line. On a two-year compounded basis, the industry grew organically by 5.4% during the third quarter of 2021. Even accounting for a few percentage points of inflation, the industry is growing in real terms despite what should be a period of heightened competition from a wide range of upstarts or retailer-owned brands.

Source: GroupM analysis of company reports

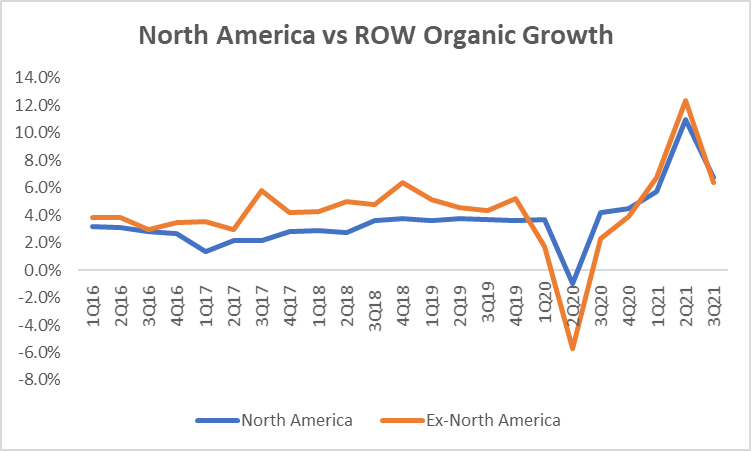

If we break out the data to look at North America vs. the rest of the world for those companies providing comparable break-outs, the trends hold up similarly well.

Source: GroupM analysis of company reports

To be sure, there remains a wide range of outcomes within the FMCG sector at the present time – pet food and beverages are growing by double digits, while personal care and home care products are growing by low single digits – and higher input costs threatens profit margins if they can’t be offset by higher effective pricing. But overall, the industry is faring quite well at the present time. Moreover, e-commerce continues to convey that companies in this space are adapting to new ways of engaging with and transacting with consumers: based on a sub-composite of companies accounting for 60% of this group’s revenue we estimate that 15% of FMCCG revenue is attributable to e-commerce sales vs. 12% in the third quarter of last year, and only 8% during 2019.

Consequently, it has been unsurprising to see the biggest “traditional” media owners reporting relatively healthy advertising trends on a two-year basis during the third quarter. For example, both of ProsiebenSat1 and RTL reported this week, providing a solid read on their mostly German business, with advertising upon a two-year average basis by mid-single digits over 3Q19 levels. BCE reported its results showing Canada’s largest TV network owner was similarly well above where it was in the same quarter two years ago. Within the US, trends are trickier to analyze, as spending tends to flow from non-Olympic quarters into those with the Games during the same year, but generally look non-negative on a two-year basis in the most recent quarter as well despite heightened reliance on e-commerce and related digital spending by many brands in the US, and despite much worse trends around cord-cutting relative to other parts of the world.

On this latter point, all of the publicly traded companies within the US pay-TV industry have now reported their third-quarter results, allowing us to see an incrementally accelerated pace of decline in video subscriptions. Each of Comcast, Altice and Verizon are experiencing high single-digit rates of decline, while according to our analysis of data from Nielsen, satellite subscriptions are probably falling by a much faster pace. vMVPDs help offset these declines, as do strategies from some cable operators such as Charter who focus more on retaining video subscribers. Still, the underlying trend continues to worsen.

Of course, what law of economics says that a change in supply necessarily drives a change in demand? Far too many individuals in the advertising industry pre-suppose that they do, independent of analysis in support of the notion. Some goods can be characterized as having “inelastic” demand, meaning the demand is relatively fixed, or at least independent of the pricing for the good either at a single point in time or over a period of time. Advertising budgets held by individual marketers for individual media can often exhibit inelastic behaviors over short and mid-term time horizons. Additionally, some marketers may choose to spend money on paid media based on their own business circumstances rather than based on the media owner’s circumstances.

Illustrating this latter point, even if packaged goods advertisers have curtailed their spending in some instances, there are still significant sources of growth driving the outcomes we are seeing. For example, this past week several large marketers focused on travel and mobility, such as Booking.com, Expedia, Airbnb, Uber and Lyft all reported their results, each with substantial increases in spending on marketing-related activities. Further, even in categories that have been negatively impacted by supply chain disruptions, such as the automotive industry, in some instances revenues are actually up because of prioritization of more expensive products. Those higher revenues generally lead directly to more significant levels of spending on advertising.

Concerns around supply chains issues aren’t going to go away any time soon because the related disruptions are certainly very real. Consequently, related comments are likely to feature prominently for any company that comes short of expectations they have set for themselves or their investors. But it’s also true that in “normal” non-pandemic periods there were always puts and takes in the economy that caused some marketers to spend more and others to spend less than they otherwise would have. To the extent that most of the industry is worried about this sort of an issue rather than a worsening of the pandemic is hopefully a reflection of the world’s gradual return to normalcy more than anything else.

On a different matter of supply and demand analysis, our attention was drawn this week to an article in Insider, which itself referenced a memo and now-public blog post https://boz.com/articles/demand-side written last year by incoming Meta/Facebook CTO Andrew Bosworth in August of last year, entitled “Demand Side Problems.” In describing the challenges of content moderation on social networks, he points back to a lecture by a high school economics teacher who described how actions related to the US War on Drugs which aimed to reduce the supply of drugs led to higher prices because “people really wanted them” – i.e. demand for drugs is relatively “inelastic”, in economics terms. From this lesson, he went on to say “It has struck me ever since that we too often try to solve demand problems on the supply side to unsatisfactory results… As a society we don’t have a hate speech supply problem, we have a hate speech demand problem.” While he states that Facebook and other social media platforms “will continue to invest huge amounts there to keep people safe” the conflation of demand for hate speech and demand for drugs is somewhat noteworthy, at least to the extent that it may inform product choices the company prioritizes.

Unfortunately, the basic premise of the post does not appear to mirror how we think the world of ideas and information works. As in the drug trade, if the value of producing and distributing an idea for a producer of that idea is high, the producer will make more of it. If the effort or costs to produce and distribute an idea are reduced (let’s say by making it easy to share or amplify the idea) while raising the benefits or revenues (perhaps by making a whole country or the whole world a market rather than a neighborhood or region) more ideas will be produced.

Meanwhile, for anyone consumer, demand for anyone idea is probably pretty low to begin with, and probably relatively “elastic” in economics terms: higher value = more demand while lower value = less demand.

More specifically, if costs to get ideas are low and falling because an algorithm can make it more efficient for that idea to find its way to an open-minded consumer, but the promise of value embedded in an idea is high, then demand can go up. Arguably, the more one sees ones’ peer-group embracing that idea, demand could go up even higher. In other words, demand for ideas is all very sensitive to the perceived value of the idea, unlike drugs where demand probably is relatively fixed regardless of value.

Ironically, the post reminds us that there are commonalities between drugs and social media, well-documented as we all now know. The commonalities between the economics of drugs and the economics of hate speech are much more limited. If they were otherwise, solutions to reduce the presence of hate speech would primarily reside in the realm of civil society rather than in the distribution and algorithmic amplification of ideas.