INTRODUCTION

Many sectors are seeing significant growth in advertising revenue, yet there are fears of recession. E-commerce is finding its place in a world where in-person activities are resuming, all while pandemic-related lockdowns in China and supply chain bottlenecks from there and war-torn Ukraine contributed to a drag on growth in the first half of 2022.

Coming off the lows of 2020 and the highs of 2021, the advertising market is settling into 2022, a year that’s seeing rising inflation, increased wages, mounting regulatory pressure on Big Tech and an overall effort by consumers and marketers to find their footing in a world that’s getting increasingly used to living with COVID-19.

Halfway through the year, we now expect advertising to grow by 8.4%, excluding the impact of U.S. political advertising (what we call “underlying” growth), slightly lower than the forecast we gave in December 2021.

Most marketers are still adding to their media budgets in 2022; a key difference between this year and last year is that the rate at which this is occurring for older marketers is simply slower, and at the same time there are likely fewer new marketers emerging.

Increased consumer price inflation in the markets we cover is expected to average nearly 7% this year, sparking fears of recession. However, we don’t see a perilous economic state. Underlying (“real,” or inflation-adjusted) growth should outpace that of 2019, even if some parts of the world do end up experiencing an economic downturn.

We now expect growth in ad revenue for pure-play digital platforms of 12% in 2022, slower than the 32% pace observed in 2021. As a major driver of last year’s gains, perhaps it should have been imprudent for anyone to expect e-commerce-related growth to keep pace with the high-flying numbers of 2021, but the relative degree of deceleration — not necessarily decline — this category of advertisers is likely having on digital advertising appears significant. Although typical large brands with well-diversified media plans may allocate half of their budgets into digital media, the average, covering marketers of all types and sizes — including many who are too small to use anything other than digital media — is much higher at 67% this year.

Television, which retains its critical, if increasingly secondary, role for larger brands, is also poised for solid underlying growth this year — at least relative to prior expectations — of 4%, continuing to rebound from the doldrums of the early pandemic. Ad-supported streaming services are likely buoying the medium as they offer marketers a similar channel to hit their reach and frequency goals, but over time those connected TV environments are likely to capture shares of existing linear TV budgets more than they will drive money toward it.

Notably, television is becoming increasingly global in ways it never was before. Mostly U.S.-based streaming services continue to invest aggressively in local-language content as they move into foreign markets and position themselves to gain audience shares from historically dominant incumbent broadcasters with geographic limits to their operations.

The impact of government policies and preferences on the ad-supported media is another increasingly important trend impacting the industry. Larger scale efforts to curb the influence of major tech companies and regulate platforms, like the EU’s Digital Services Act, are taking aim at Apple, Google and Meta via de facto or de jure efforts to break up those companies. Other regulatory initiatives are popping up in America, too, with some at the state-level taking a different, politically charged approach by attempting to codify into law that platforms cannot censor content on their sites as they would like.

2022 Global Mid-Year Forecast

Click here to downloadGLOBAL ECONOMIC BACKDROP

There are numerous problems at the forefront of daily life in many of the world’s largest advertising markets, with concerns about the consequences of war in Ukraine, additional global supply chain disruptions associated with pandemic-driven lockdowns in China, ongoing input cost inflation and, perhaps most visibly in many parts of the world, higher prices for consumers. Prices for food and other goods have been consistently rising at unusually elevated levels for the better part of the past year in many places leading to headlines of inflation and the potential risk of recession.

Looking at data covering the month of April 2022 and using the dominant measures of inflation on a year-over-year basis, prices rose in the U.S. by 8.3%, while in the Euro Zone rates rose by 7.4%. In the U.K. it was 9.0%, and in Canada it was 6.8%. However, it’s not quite so severe in every major market: In China inflation most recently ran at 2.1% while in Japan the figure was 2.5%, and in Australia it’s only 3.7%. In two other large markets, Brazil and India, inflation was high to be sure — up 12.1% and 7.8%, respectively — although in those countries relatively higher levels of inflation have been much more common in the past, so consumers and businesses are somewhat more experienced at managing it.

On a weighted average, markets we track in This Year Next Year are expected to experience inflation of 6.9% during 2022, up from 3.7% in 2021 and above levels that more typically ran in a 2%-3% range in recent decades (although we note that this measure of inflation amounted to 5.1% in 2008). Over the past six months, expectations have shifted significantly.

… markets we track in thisThis Year Next Year are expected to experience inflation of 6.9% during 2022 …”

For many individuals and policymakers in North America and Europe who grew accustomed to negligible levels of inflation, the current environment represents a negative surprise despite actions and circumstances that were plainly likely to cause this outcome. In response, relevant central banks have raised or have signaled they will raise interest rates from historical lows, leading to concerns that higher costs of capital will constrain economic activity before prices are under control. This, in turn, has led many to fear a stagflationary recession.

However, for as negative as all these factors are, economic conditions are actually not quite so bad as headlines might suggest.

Interest rate increases have been low in absolute terms. They have essentially gone from zero to 1% or 1.5% in the U.S., Canada and the U.K., while in Europe that equivalent figure remains at zero. By any standard, rates are low and are likely to remain so in an absolute sense for the foreseeable future.

Perhaps because of the room that central banks have to tighten without constraining, consensus expectations from investment bank economists continue to call for real economic growth this year and next, meaning that even if some markets see a recession (technically defined as two consecutive quarters of economic decline), most believe growth will prevail for the year on the whole around the world.

Recession: When a country’s economy experiences negative real GDP for two consecutive quarters. Common indicators include high unemployment, lower spending and wages, high inflation, lower retail sales and manufacturing as well as high debt.

More specifically, as of the end of April consensus estimates among bank economists called for 3.5% real growth in global economic activity during 2022. While this is down from expectations made in January (which called for 4.3% growth), we note that this would still be higher than 2019’s 2.9% real growth rate. For those who can remember a period of time prior to the pandemic, that was a year with fairly strong advertising growth trends. To this real growth rate, one can add higher levels of inflation and we can reasonably expect global gross domestic product (GDP) to approach or slightly exceed double-digit gains in nominal terms this year.

Consumer spending will undoubtedly drive most of this growth. Higher prices are helping to drive such spending up, as wage gains and stored-up savings are allowing consumers to pay more than they might otherwise like to for the goods and services they want, many of which they may have refrained from buying because of pandemic-era conditions. In many markets we can see data that shows how savings rates rose throughout the pandemic, when many governments around the world offered stimulus payments or salaries in lieu of working in order to limit the spread of COVID-19 while keeping economies afloat. In aggregate, consumers simply didn’t spend as much as they might have during that period. And while many individuals needed and benefitted from a cash influx at the time, aggregated savings levels also rose significantly as a result.

Inflation: Inflation measures capture changes in pricesfor evolving baskets of goods and services in an economy, or within specific regions of a given country. CPI (Consumer Price Inflation) or similar measures (HCPI — “Harmonized Consumer Price Inflation” — or a Personal Consumption Expenditure inflation index) are primary ways in which policy-makers track inflation. As inflation corresponds to increases in price, it can cause a reduction in purchasing power if all else is held equal.

To illustrate, consider that during the five arguably worst quarters of the pandemic (2Q20 through 2Q21) the average savings rate amounted to 16% in Australia, the U.K. and Canada, 17% in the U.S., 22% in France and 25% in Germany. During the preceding five quarters savings were measured in the teens in France and Germany and single digits in the other markets mentioned here.

At the same time, low-interest rates afforded property-owning consumers an opportunity to refinance their assets, reducing expenses further and adding significant pools of capital to cash balances, especially in the United States. Not only did these consumers save significant amounts of interest expenses on the massive $2.3 trillion of mortgages that were refinanced during 2021, but, during that year, $275 billion of equity was tapped via mortgage cash-out re-financings, money that can now be drawn upon to soften price increases. For a sense of scale, all Americans’ personal income amounted $13 trillion in 2021.

Gross Domestic Product: Measures the total value of goods and services produced by an economy.

But it wasn’t only savers and property owners who benefitted financially from recent circumstances in high-inflation markets: In at least some instances, wage earners have also seen significant gains as labor markets have remained tight. In the U.K., average wages grew by 7.0% in the first quarter, for example. In Germany, first-quarter wages rose 4.0%, following on three additional quarters of solidly mid-single-digit gains, making it the strongest period of wage growth in a decade. In the U.S., average wages earned across all people rose by 4.9%, a level that was below CPI inflation, but wage gains for the lowest 10% of wage earners — i.e., those less likely to have much in the way of savings or assets to fund shortfalls — actually rose much faster, growing by 9.3% during the first quarter of 2022. This represented an inflation-beating trend that has broadly occurred over much of the past decade for this group. The lowest quintile of wage-earners has generally experienced similar trends since 2016. Tight labor markets are likely to support such trends for the foreseeable future.

Perhaps as a result, during their first-quarter earnings results presentations in April and May, companies from across a wide range of industries emphasized that consumers were tolerating price increases and demonstrating relatively “inelastic” demand. Even when there were supply chain issues, manufacturers chose to prioritize higher value (and higher-priced) products and generally passed input cost increases along to customers in the process.

Even when there were supply chain issues, manufacturers chose to prioritize higher value (and higher-priced) productsand generally passed input cost increases along to customers in the process.”

It’s useful to consider what expectations looked like for the year 2022 if we go back in time to the middle of 2021, when the end of the pandemic appeared close, and inflation was not yet a significant concern. At that point, consensus expectations for real (inflation-adjusted) GDP growth in 2022 amounted to 4.5% with inflation expectations of nearly 3%, for better than 7% growth in nominal terms. Fast forward to the present where expectations for 2022 growth in real terms amount to more than 3% with inflation expectations of around 7%. As a result, nominal growth is implicitly forecast at around 10% during 2022. As This Year Next Year tracks nominal advertising revenue growth, these nominal figures are the data we are ultimately paying the most attention to and represent the singular economic variable to which one might most appropriately tie advertising growth.

Similarly, expectations for nominal growth in 2023 are actually higher now than they were last year, although, of course, we recognize the weaker expectations for real GDP growth do reflect a less desirable outcome than might have been hoped for at this point in 2021.

Inelastic Demand: Inelastic demand is often used to describe a situation when changes in prices for goods or services do not lead to changes in demand. When demand is inelastic, consumers will not change the quantity of goods and servicesthey buy despite higher prices.

With these conditions, it should be unsurprising if most marketers would generally continue to increase their budgets for advertising roughly in line with revenue growth. And for the most part, the largest advertisers have reported revenue growth in the first quarter of 2022, with consensus expectations for growth as of June only slightly weaker for this group than it was prior to the war in Ukraine. The subsequent advertising increase occurs in part because many companies manage these budgets in a relatively mechanical manner, and also because some need to sustain or expand their media presence in order to justify higher prices. Another rationale for increasing advertising is to avoid loss of share to competitors who, in a growing economy, will almost certainly collectively advertise more to capitalize on the expected growth in consumer spending.

Input Costs: Input costs refer to costs for the materials, labor and overhead required to produce a good or service.

THREE KEY DRIVERS OF ADVERTISING

At the same time, three key secular drivers of advertising we have identified that contributed to elevated growth during 2021 are still impacting current trends, although these “tailwinds” are likely reduced this year compared to last year.

NEW BUSINESS CREATION AKA CREATIVE DESTRUCTION

First, data generally shows ongoing increases in the numbers of businesses — by definition, almost all of which are small — in different countries, with levels that have been elevated since the end of the first full quarter of the pandemic. While growth rates have declined year-over-year during each month of 2022, they are still substantially above levels observed in 2019. New business formation is an important engine of advertising growth because individual businesses typically budget some amount of advertising if only to tell the world they exist. More importantly, it seems likely that these newer cohorts of small businesses have higher advertising-to-revenue ratios than older businesses, serving as a boost to advertising growth (and one that should continue, albeit at a more moderate level). While this is a theory, to be clear, it appears to be supported by anecdotal observations of the increasingly online nature of newer businesses relative to older ones, and the propensity of businesses that are based online to spend money in pursuit of website traffic to a greater degree than offline businesses do with offline media.

New business formation is an important engine of advertising growth because individual businesses typically budget some amount of advertising if only to tell the world they exist."

VENTURE CAPITAL AKA GROWTH AT ANY COST

Second, we note the role of venture capital, as these pools of capital have helped fund significant numbers of massively scaled companies, with many of them similarly possessing advertising expense-to-revenue ratios that are much higher than incumbent competitors. It appears increasingly clear that venture investors, and many of the companies they fund, will be more disciplined when it comes to their investment choices and operating costs in the current environment of economic risk and higher capital costs (i.e., interest rates). There has been more than one example of this in recent news, and yet these marketers will undoubtedly continue to invest in advertising in order to drive growth, at least so long as it is profitable growth in the near term.

CHINESE MARKETERS ADVERTISING ABROAD

The third secular factor we have pointed to relates to Chinese marketers advertising abroad, primarily using self-service advertising tools on global platforms. Among the three listed here, this segment of marketers appears most likely to serve as a drag on growth in 2022. It is difficult to know the degree to which lockdowns in China directly caused a negative impact on advertising around the world, if they did at all. While directly connecting those globally-oriented Chinese manufacturer-marketers to current advertising trends is difficult, we can point to Chinese exports as an illustrative data point conveying the growing role of China in global markets, despite broader de-globalization trends in some markets. Exports grew by a mere 3.9% in April and just over 12% for the first four months of the year. This represents a noteworthy deceleration of growth from 2021 when monthly export volumes typically expanded well in excess of 20%. However, to the extent the deceleration is temporary, as conditions begin to revert toward “normal” in June, export activity may yet see more meaningful growth.

THE IMPACT OF NEW GOVERNMENT POLICIES

Beyond the broad changes in the economy that have generally evolved independently of any one government’s choices, it is important to contemplate the degree to which regulatory policies are positioned to impact the media business this year, next year and beyond.

When it comes to digital media platforms, in recent years it has been evident that the primary driver of change would be the EU, although American legislators and policymakers have more recently started to catch up. We can point to a vast array of efforts by those governments to regulate three of the biggest sellers of advertising by proposing or beginning to implement laws that are intended to constrain the choices those companies make, and to generally limit their market power. We see this in terms of how Alphabet’s Google and Meta’s Facebook sell ads and engage with other parts of their ecosystems, how Apple and Alphabet work with app developers or how Amazon works with third-party merchants.

Collectively the direction of travel seems relatively certain with policymakers constraining actions, forcing break-ups or creating conditions where break-ups become more appealing than the status quo. Most importantly for our purposes, while any of these outcomes introduce certain problems or risks for the industry, it seems very unlikely that any of those actions will impact overall advertising growth rates. We generally retain the view that while constraints such as those described earlier may impact where money goes within the ecosystem, we don’t believe they will impact marketer budgets by very much, if at all. Moreover, we are predisposed to the view that when industries become more regulated, larger companies are generally better able to thrive within the spheres in which they are regulated relative to smaller competitors.

When it comes to digital media platforms, in recent years it has been evident that the primary driver of change would be the EU, although American legislators and policymakers have more recently started to catch up.”

STATE-LED POLICIES IN THE U.S.

While the issues highlighted before are moving forward in many places, there are other more uniquely American issues that have begun to bubble up from individual states in recent months, as with efforts to prevent social media platforms from blocking individual users or specific types of content. If these efforts prove successful, they could have implications for markets around the world as all the major global platform owners, except Bytedance, are U.S.-based and are likely to think of their home market’s standards and offerings as baselines for everywhere else.

As an illustration of these kinds of initiatives, in 2021 the Texas state government passed a law, HB20, that would make it illegal for any social media platform with 50 million or more monthly users to “block, ban, remove, deplatform, demonetize, de-boost, restrict, deny equal access or visibility to, or otherwise discriminate against expression,” potentially meaning that all content, including hate speech and spam, must be displayed equally. The law was initially blocked by a federal district judge, but in May 2022 an appeals court allowed it to go forward with the supposition that social media platforms were not “websites” and, because of their market power, should instead be categorized as “common carriers,” a distinction requiring them to serve all customers and carry all lawful traffic. For the time being, the U.S. Supreme Court has overruled the appeals court and reinstated the federal district court’s block, but the case appears likely to return to the highest court’s docket in the future with an uncertain outcome.

Texas is far from alone in its efforts, though. Also in 2021, the government of Florida attempted to prevent large social media companies from “deplatforming … a political candidate or journalistic enterprise.” Up against a different federal appeals court, an injunction against that law was upheld. Meanwhile, in Ohio, a legal effort from that state’s attorney general aims to determine that Google’s search engine is also a common carrier, under the premise that the “goods” Google transports are information. In the U.S. media industry, such rules have been applied to cable operators, essentially obliging them to carry broadcasters whose programming they might not otherwise have chosen to distribute, suggesting it is not at all far-fetched that first amendment rights might be overridden when it comes to digital media platforms.

One reason these cases matter is that, in the United States, social networks have traditionally been able to rely on Section 230 of the 1996 Communications Decency Act to allow them to handle user-generated content and filter harmful language. However, if the above efforts succeed, they could open platforms to litigation if the platforms do not adhere to the responsibilities that might follow from the proposed laws. Questions around how the world’s digital media giants might adapt and how marketers would respond to environments that would be decidedly less desirable than they are today remain unclear.

European efforts to toughen these standards are, by contrast, much more ready to move forward in a different direction, with the EU’s Digital Services Act likely to come into effect by the end of 2023. An update to the bloc’s e-Commerce Directive from the year 2000, the law is primarily intended to combat illegal content (i.e., what’s illegal offline should be illegal online) and disinformation at a European rather than national level. The imposition of heightened standards from Europe for European consumers on the global platforms could contrast with those that might evolve in the U.S., creating very different experiences for consumers and advertisers in the two regions.

CHANGES TO MOBILE TRACKING AND MEASUREMENT AT APPLE

We might expect more commonality across the two regions with respect to consumer privacy not only because Europe and certain American states have continually pushed laws in this direction in the name of human dignity, but also because Apple has taken coinciding stances and implemented changes limiting the availability of data generated through its mobile operating system. As a company in the crosshairs of regulatory action and active competition with Apple as an operating system provider, it was always inevitable that Google would follow suit with similar actions, as they announced they would earlier in 2022.

Developers of apps — including social media services, some of whom are primary competitors to Apple for different products and services with an interest in conveying the presence of heightened competition in the market — have already claimed to experience significant economic harm from the changes Apple made around this time last year. We remain highly skeptical that industry-wide spending was impacted in a material way and believe company-specific impacts are probably less significant than are commonly conveyed.

To illustrate why, as we note later in This Year Next Year, digital advertising grew faster around the world than in any year since 2007, a period where digital advertising was a mere 8% of the size it presently is. Our analysis of quarterly growth rates for the world’s largest digital platforms during 2021 shows no material difference in growth rates over multi-year periods of time (a better way to assess growth rates while separating out the statistical noise and quirks of the depths of the pandemic during 2020).

While it’s true some platforms failed to grow as fast in periods following the implementation of Apple’s changes as they did in prior periods, it’s impossible to assess the degree to which such company-specific problems were instead due to some combination of:

- budget saturation for certain segments of customers (if, for example, small businesses shifted all of the budgets to a platform that they plausibly could have),

- unique customer-segment skewing growth trends (heightened exposure to a category such as e-commerce, which was poised to decelerate during the latter part of 2021 and early 2022),

- user trends (limiting available inventory) or

- product offerings (an inability to provide sufficiently evolved measurement capabilities to account for the new data limitations).

The loss of data fidelity itself is almost never a reason for budgets to fall or decelerate. Data that marketers have access to is rarely “perfect,” and the choice of signals they use to drive specific budgets to specific media owners or specific platforms always depends on a wide range of subjective choices. These include the appropriate time horizon to account for between awareness and purchase, the degree to which inherently poorly trackable elements of marketing such as word-of-mouth impact outcomes, similarly limited tracking of word-of-mouth activity for competing brands, qualitatively evolving consumer preferences and expectations, creative and brand choices and many other factors. Moreover, a heavier investment in human-driven data analysis with less data will likely drive better outcomes than less human analysis of greater volumes of data.

Digital advertising grew faster aroundthe world in 2021 than in any year since 2007, a period where digital advertising was a mere 8% of thesize it presently is.”

CHINESE GOVERNMENT ACTIONS

Changes to policies in China, while reflecting some common underlying trends, have gone much further and illustrate how changes can alter the growth rate of the advertising industry in ways that neither the EU nor the U.S. would ever contemplate. Several of the Chinese government’s actions significantly impacted the ability of individual categories of marketers to advertise or otherwise engage with consumers.

In the sphere of data and privacy, where the trend in China has been similar to what has been observed elsewhere, two new laws were enacted in the second half of 2021 (the Data Security Law and Personal Information Protection Law). These laws built on 2017’s Cybersecurity Law to govern how data is used, including limitations on the export

of data along with certain privacy-based protections. In other spheres, trends have been decidedly unique to China. Last August saw the announcement of an array of efforts to diminish the role of fan-driven celebrity-focused culture while at the same time imposing new content standards. Related rules effectively sought to contain what had been

a relatively open environment for consumers and brands online. Other restrictions included significant time limits imposed on minors playing video games online and the near elimination of online tutoring — a significant category for sellers of advertising.

POLICIES PROMOTING LOCAL LANGUAGE CONTENT AND PRODUCTION

While the degree to which changes have been suddenly implemented in China is somewhat unique, it is worth recalling that active policies intended to impact culture are actually common around the world. In many countries, a recent focal point has been the American-based streaming video providers, especially Netflix and Amazon Prime Video, whose scale typically dwarfs the size of other services in any given market. Obligations for streaming services to invest in domestic, local language content productions are increasingly common around the world. For example, in May, Switzerland voters supported via referendum a tax that would oblige foreign streaming services to spend 4% of revenue on local productions, matching the obligations local broadcasters have. Also in May, the Danish government imposed a similar 6% tax on the same entities. These figures are much lower than those imposed in other countries like France and Italy, but the broad thrust of the effort in markets around the world is similar.

One of the potentially under-appreciated consequences of such initiatives is that they arguably help to reinforce trends that were already underway. Audiences around the world have demonstrated interest in content from foreign markets in foreign languages. As global streaming services invest in greater volumes of productions in greater numbers of languages, they will inevitably find greater numbers of global hits that will make their platforms relatively more appealing than services whose scale is geographically limited.

Restrictions included significant time limits imposed on minors playing video games online and the near elimination of online tutoring — a significant category for sellers of advertising.”

In aggregate, U.S.-based streaming services could very soon spend more on local language content in many individual countries than those countries’ historically dominant broadcasters. To the extent that there is a direct relationship between share of spending on content and share of viewing, the extra resources the globally-oriented streaming services deploy into content will only serve to grow their audiences. Single country television network owners who concentrate their efforts on their home markets and attempt to serve as “national champions” rather than pursue bigger global opportunities will find their businesses at risk of shrinking as a consequence.

Obligations for streaming servicesto invest in domestic,local language content productions are increasingly common around the world.”

BLURRY MEDIA DEFINITIONS AND DIGITAL EXTENSIONS

Twenty or more years ago, defining a medium was a relatively simple matter. Print was print, radio was radio, television was television, etc. The internet changed everything, as digital extensions of traditional media proliferated. The New York Times begat NYTimes.com and the likes of Buzzfeed emerged as sources of sometimes very serious — and competitive — journalism. Radio stations began streaming and services like Spotify provided functionally comparable alternatives.

Similarly, TV networks started to offer their programs on the internet and some, such as NBC, ABC and Fox in the United States, founded a dedicated service in Hulu. Over time they and others invested in original productions that were practically like traditional TV. When advertising was involved, the execution of campaigns was, of course, very different when comparing traditional and digital forms of a given medium, with the digital forms generally more similar to each other regardless of the type of content involved.

In most ways these distinctions weren’t important to consumers, for whom the new was arguably just a continuation of the old. And this view was reinforced for marketers by pragmatic media owners who commonly bundled the sales of digital platforms with their traditional offerings.

It was always the case that there was some blurriness where TV-based networks had some print-equivalent content and related ad sales on their websites produced by news divisions. Similarly, there was ambiguity as ostensibly pure-play digital platforms made some professional video or print-like content. But these initiatives were relatively small and, for practical purposes, indistinguishable from the media owner’s core focus and alignment with traditional media categories. Such observations historically informed why the data contained in This Year Next Year has included digital extensions of traditional media alongside traditional media in our headline numbers.

However, efforts by media owners to establish their offerings across different media types and a willingness among marketers to revisit what gets included in their definitions of media for planning and budgeting purposes appear to be increasingly significant. Traditional print publishers are building on their digital content offerings to include audio products such as podcasts. Digital platforms like YouTube that rely on user-generated or semi-professional content are increasingly considered to be comparable to television and, before long, a more significant share of their revenue will come from television-based budgets.

To be clear, we think that the notion of including digital extensions as subsets of traditional media is still the appropriate way to think about media plans, media budgets and ad revenues at an industry level, at least in most instances. Podcasting is still a very small share of newspaper publisher revenues, and it will be many years before YouTube represents more than a small share of total TV advertising. Still, we highlight that the definitions we use today and the buckets we group media into are far from universal, and far from permanent.

MEDIA CONCENTRATION

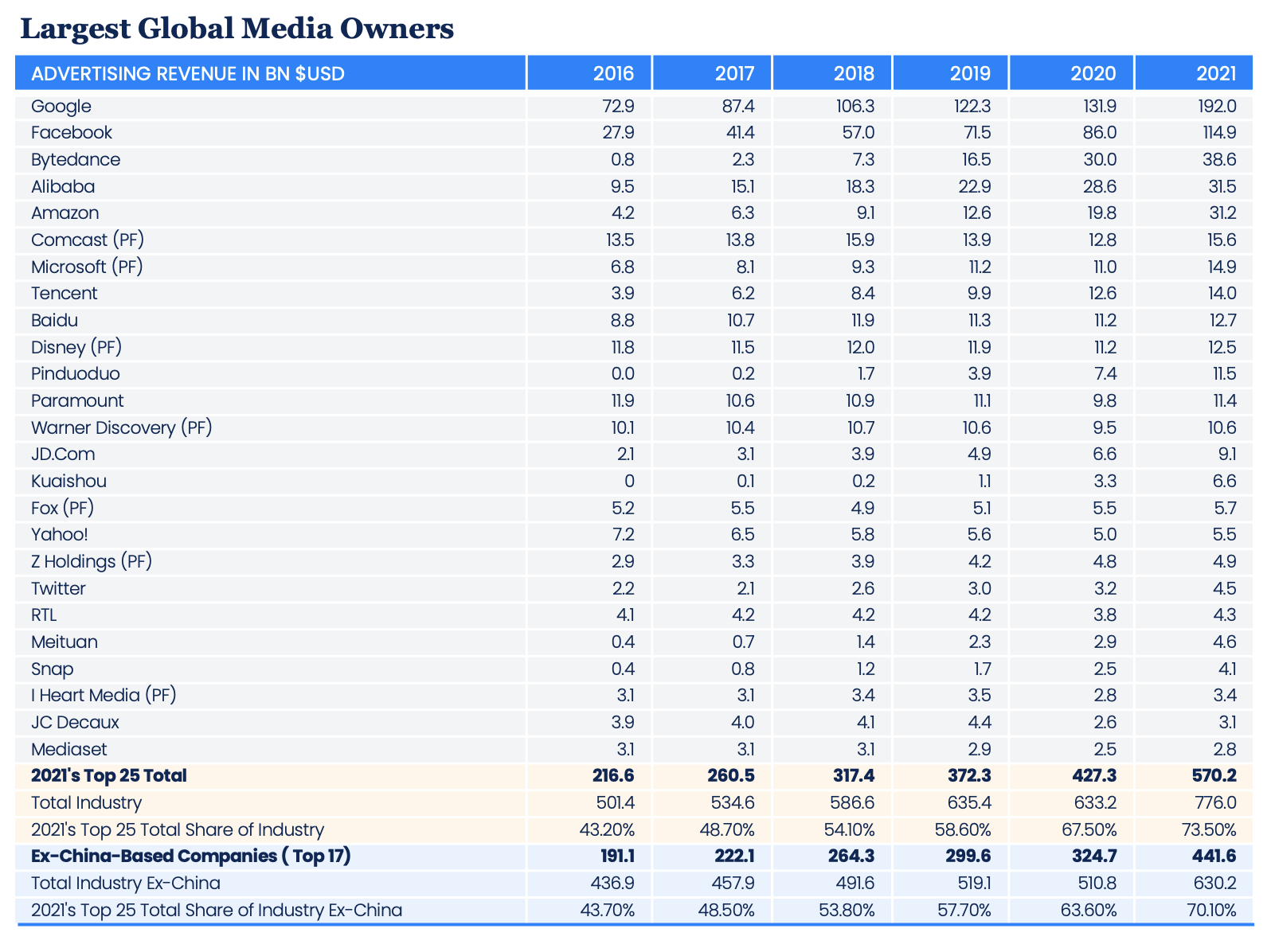

At around this time last year, we established data related to the global advertising revenue share held by the world’s largest media owners. We now have updated data to cover the revenues these companies generated during 2021 and our revised historical estimates for advertising in every market around the world.

Although some of the specific figures have changed, the broad trend continues much as we illustrated last year, with the world’s largest media owners accounting for a growing share of the industry. Specifically, we now estimate that the top 25 media owners represent 74% of global advertising.

Outside of China, the top 17 companies represented 70% of global advertising in 2021, an increase from 44% in 2016. Importantly, while eight of the top 25 are Chinese-based media owners, their ad revenue remains largely mutually exclusive and collectively exhaustive with Chinese-based media owners generating almost all their revenue in China, and almost no ad revenue in China generated by non-Chinese companies reaching Chinese consumers in China. TikTok owner Bytedance is a notable, yet relatively minor, exception with only a small, if rapidly growing, share of its revenue outside China by our estimates.

Looking at the data a different way, consider that the top five sellers of advertising in 2021, a group including Google, Facebook, Alibaba, Bytedance and Amazon, generated $408 billion in ad revenue, or 53% of the global total.

Ten years earlier, in 2011, the top five advertisers would have included Google, Viacom and CBS (which we include on a combined basis, given their common controlling ownership even then), News Corp and Fox (similarly combined here), Comcast and Disney. With the businesses as they existed that year, those companies had a combined total of $79 billion in advertising, or 20% of the global total.

One critical aspect of our analysis of market share changes is difficult to quantify with precision but is conceptually easy to consider. So, how, specifically, do we define concentration?

If we were to take our global analysis of country or market share all the way back to 2001, 1991 or any time before, we can imagine that the then-25 largest global sellers of advertising would have had a dramatically smaller share of the industry in any given geography. Among them would surely be many large country broadcast network owners, yellow pages publishers and postal services companies as providers of direct mail-based media. However, such a global analysis would have been essentially meaningless as very few would have operated outside of their home markets. By contrast, among today’s top 25, almost all of those not focused on China operate in and have realistic ambitions to grow around the world, especially those with digital platforms that can more easily launch in country after country without the type of regulatory prohibitions that would have blocked globalization efforts from analog predecessors.

Arguably, if we were to look at concentration in 2001 or 1991 the right way to do so would have been at the single country level, where we can argue that levels might have looked similar to those shown at a global level today. Taking it a step further, if we were to look at concentration at the local market — city or other narrow regional level — and look at the level of concentration the typical marketer might have experienced with their own geographically-limited operations, we might find that even then only a handful of companies accounted for practically all of the media from which a marketer bought.

Given the nature of business in such eras, concentration was probably better defined at that local level. The competitive “choice” for marketers of local monopoly newspaper, local monopoly yellow pages publisher or national monopoly postal carrier is arguably not much different than the three media owners most smaller businesses can realistically employ today, with Amazon, Facebook and Google representing the sole media channels for many.

If there is a difference now it is that those three companies at least offer businesses a significantly greater ability to market themselves nationally or internationally than their predecessors did a generation or two ago. This is not to say that concentration is too high or too low at the present time, but to highlight that the flavor of concentration as it stands today is likely better for most small businesses than it was in earlier times, that is without considering relative effectiveness or other social impacts.

For larger companies, the nature of concentration can be viewed as similarly preferable relative to its form in prior decades, with a relatively wide range of partners to prospectively work with and global scale to both learn from and extend with. Many individual marketers will sometimes express that they feel their choices are limited or constrained, but arguably this is because the specific marketing KPIs or other goals they set for themselves are constraining. This often occurs because of the time it can take to reorient a marketing organization and related budgets to capitalize on different media opportunities.

For sellers of advertising who feel that they are threatened by the triopoly or by the U.S.-based media conglomerates, we argue that the issue is not necessarily that the industry is becoming more concentrated. Instead, the “problem” is that the media industry requires more investment in engaging content, both at home and abroad.

It’s likely true that this world brings with it lower — if still positive — profit margins for media companies that invest against the future, but it does so with significantly bigger scale for those who attempt to pursue it. The best solution at hand for any given media company is to look for ways to become more global and to plan for a future that requires more investment in growth. Such choices will prove more durable relative to those that favor “harvesting” profits based on a historical industry structure that no longer exists.

CONTENT SPENDING

On our updated estimates of spending on video and related content production by the world’s largest media companies at the global studio, network and streaming service level (i.e., not considering spending by traditional distribution businesses), we estimate that Comcast was the biggest globally with approximately $20 billion of spending during 2021. We are mindful that accounting choices companies make may impact the specific figures associated with each company’s GAAP content expenses, and a range of other timing preferences may impact when cash costs are incurred to produce a different cash-based measure of content expenses. And, of course, there can be substantive differences in assessing content costs when companies have a different mix of content produced in-house for use in-house versus content that is licensed from others versus content that is produced in-house for licensing elsewhere.

However, the broad thrust of the data tells the same story: A handful of American companies utterly dominate content production at a global level. Moreover, as we described earlier, their investment is not only in English-language content as a significant and growing share goes into content produced specifically for other countries.

We believe there is a real relationship between share of spending on content and share of viewing. Consider that in the U.S., Netflix accounts for approximately 6%-7% of all TV viewing, according to Nielsen, and assigning GAAP content costs in proportion to the company’s domestic revenue, it incurred related expenses of around $5 billion.

If we consider spending by U.S. MVPDs (including cable, satellite and virtual MVPDs) we can estimate there was $66 billion in programming spending last year. If we instead consider spending by national TV networks and local broadcast stations, we could calculate a roughly similar number. Adding spending by Netflix and other services with direct-to-consumer offerings, this data shows that Netflix probably accounts for around 7% of total spending to capture its roughly similar share of viewing.

The logic behind such an outcome should be unsurprising: When a content packager (such as Netflix, another streaming service or a TV network) produces or buys hundreds or thousands of content assets, some of them will randomly become massive hits, some will be ignored, and the rest will help to fill out a library that in aggregate captures a certain volume of viewership. If content is priced fairly — meaning one packager doesn’t systemically overpay relative to everyone else, even if they might have the effect of driving industry-wide prices up — then we might assume that on average a given amount of spending on content will result in a relatively predictable audience volume. We can’t predict when a given service will develop a zeitgeist-dominating property or an overhyped bomb, but we should be able to predict the overall consequences.

There is a real relationship between share of spending on content and share of viewing."

Applying this logic to other markets, knowing that the U.S.-based streaming services have begun to deploy significant volumes of capital to local-language productions, we can anticipate that media companies who are solely focused on modest incremental investments for traditional and streaming services in years ahead are bound to lose meaningful viewing shares and diminish in importance over time unless they make more significant efforts. Too few non-U.S.-based TV network owners are investing sufficiently in their home markets, let alone globally, to compete in an industry that is becoming much more global than it ever was.

The consequences will impact marketers, as well.

On the one hand, globally-oriented marketers are relatively better-positioned for the world that will emerge, because they will be able to establish global relationships with the U.S.-based streaming services. This will be relevant in terms of identifying best practices in working with these services, possibly developing content to be deployed on them or establishing business plans and budget commitments.

Globally oriented marketers are relatively better-positioned for the world that will emerge because they will be able to establish global relationships with the U.S.-based streaming services."

On the other hand, despite platforms like Disney+ launching their ad-supported offerings and Netflix announcing it’s planning to do the same, it is unlikely that ad loads on streaming services will come anywhere close to the ad loads traditional providers of TV services offer. Consequently, the capacity of television to support the reach and frequency goals that most marketers require will be increasingly compromised. Although television will remain uniquely impactful for marketers who use it relative to alternatives, the greatest impact for those kinds of companies will undoubtedly come from heightened investments in broader brand initiatives, including superior consumer insights, better creative ideas and ongoing presence across a range of consumer touchpoints.

We can anticipate that media companies who are solely focused on modest incremental investments for traditional and streaming services in years ahead are bound to lose meaningful viewing shares and diminish in importance over time unless they make more significant efforts.”

ADVERTISING INDUSTRY GROWTH

Generally, we hold the view that so long as real (inflation-adjusted) economic growth is positive, inflation should be a positive contributor to advertising growth. If economy-wide inflation runs hotter than we expect this year, so too should our forecasts for advertising because of the general impact inflation has on advertiser budgets. This should be true so long as any central bank interest rate increases do not cause reductions in investment or other sources of company expansion.

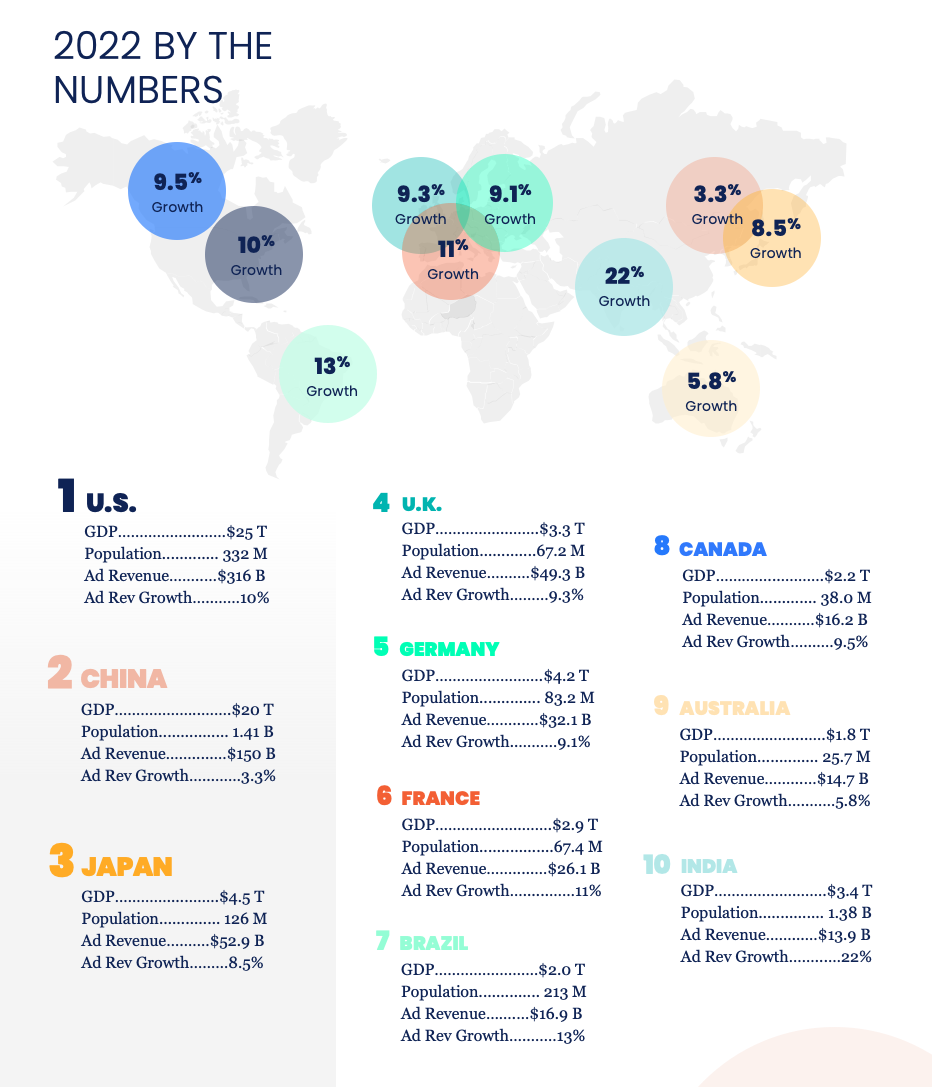

With all of this in mind, we expect advertising to grow around the world by 8.4% in 2022, excluding the globally distorting effects of U.S. political advertising. This is slightly below our prior 9.7% forecast from December, a change driven primarily by deceleration in China, which is now forecast at 3.3% versus 10.2% in December of last year. One can interpret the data as slightly negative in direction on a relative basis, but only marginally so, as expected growth on an inflation-adjusted basis is still positive, and similar to what we saw in many years during the 2010s.

Of course, we emphasize that with growth now estimated at 25% for 2021, an upwardly revised estimate of the overall base of digital ad revenue in prior years, overall expectations should still be viewed in a positive light. Within digital advertising, the biggest drag was likely e-commerce-based activity where deceleration should be unsurprising (given the outsize growth in 2021), even if the degree of the slowdown is stronger than expected.

We expect advertising to grow around the world by 8.4% in 2022, excluding the globally distorting effects of U.S. political advertising.”

DIGITAL

Pure-play digital advertising platforms should grow by 11.5% on an underlying basis during 2022 versus our previous 13.5% forecast. The secular factors described elsewhere in this document (i.e., business formations, venture capital and China-based advertisers) remain as growth drivers but shifts from existing advertisers — incumbent brands or those who historically prioritized television — are a secondary source of the growth. Overall, digital advertising on pure-play platforms (not including spending by advertisers on digital extensions of traditional media and excluding U.S. political advertising activity) represents 67% of the industry’s total this year and should amount to 73% in 2027.

Only five years ago that figure was 43% and ten years ago the figure was 20%. It is worth noting that total advertising activity has more than doubled in size over the past decade, driving most of digital advertising’s growth to a figure that we estimate will amount to more than $563 billion in 2022, covering all digital-only platforms. Under a broader definition of digital advertising, which includes traditional media’s digital extensions, we estimate the industry will account for $618 billion in 2022, or 73% of its total.

RETAIL MEDIA & SEARCH

Within digital advertising, we think retail or e-commerce-based media growth should generally outpace all other major forms of digital media in years ahead. The world’s larger social media platforms will likely collectively grow on pace with the broader digital media sector, although TikTok at minimum should continue to take share so long as its usage levels remain high and national security concerns are not acted upon.

Search continues to solidify its role and massive size, with Google continuing to account for almost all related activity.

We think that retail or e-commerce-based media growth should outpace all other major forms of digital media in years ahead.”

TELEVISION

Meanwhile, after recovering during 2021 with double-digit growth, television appears poised to produce more limited, if still solid growth (excluding the impact of U.S. political advertising) with a 4.4% gain for the medium overall during 2022. We are increasingly persuaded that some incremental growth has come to television from new advertisers enabled by the advent of connected TV. Put differently, the likes of Pluto, Tubi, Roku and other single-country streaming offerings have probably caused some money that might otherwise have gone into digital media platforms to shift onto consumers’ TV sets instead.

In total, we estimate that global Connected TV+ advertising amounts to $21 billion in 2022, up by 24% over 2021 and accounting for 12% of all TV globally.

However, we don’t believe this causes a major step-change in the growth trajectory of television: TV growth in its broadest definition — including Connected TV+ — is poised to flatten in the coming years. Connected TV environments, including digital ad inventory from streaming services, will capture shares of existing budgets much more than they will drive new ones into the industry.

Recent announcements from Disney and Netflix related to plans to offer advertising-supported tiers for some of their subscribers on their flagship services will provide some marketers with confidence that television will continue to satisfy their reach and frequency goals and encourage them to retain large budgets with the overall medium. However, it is unlikely that most users of streaming services will do so on an ad-supported basis.

Further, ongoing declines in viewership of television paired with increasing levels of cord-cutting continue to compromise the relative utility of the medium, as the world’s largest marketers historically relied upon television to essentially reach everyone with their campaigns. So, while it remains the case that television is better than many alternatives for the purposes of satisfying reach and frequency goals, its reduced effectiveness will only encourage marketers to explore alternative media and marketing strategies.

Notably, for many marketers, YouTube will look increasingly like a substitute to television, at least for those who believe their traditional TV creative is appropriate to use on YouTube, and for those who care more about customer segments rather than the need to borrow brand equity of the content where their advertisements run. But ongoing challenges in the form of integrated measurement across linear, streaming and YouTube, as well as marketing operations and workflows, may limit the flows of spending across these media types.

In total, we estimate that global Connected TV+ advertising amounts to $21 billion in 2022, up by 24% over 2021 and accounting for 12% of all TV globally.”

OUTDOOR

Meanwhile, outdoor advertising continues to rebound as it progresses toward pre-pandemic levels in most parts of the world. Early 2022 has been strong as audiences have returned, people spend more time enjoying life out of the home again and new movement patterns emerge. New brands, marketers in the travel category and advancements in data-driven targeting are helping drive growth, too. However, the aforementioned economic challenges still present risks.

Although we forecast a slight decline in outdoor advertising during 2022, this is entirely because of current weakness in China — formerly the world’s largest OOH market. Excluding China, growth should amount to 14.3% this year as many markets have approached or are soon to exceed their pre-pandemic highs.

Digital OOH inventory continues to represent the bulk of growth now, with nearly a third of share at present.

We expect outdoor to exceed its 2019 volumes in 2024, indicating that much of the growth we are seeing at present can still be characterized as recovery driven.

We expect outdoor to exceedits 2019 volumes in 2024, indicating that much of the growth we are seeing at present can still be characterized as recovery driven.”

AUDIO

Audio in its broadest definition may still need more time to fully recover, if it ever will, as the industry remains substantially oriented around locally constrained advertisers who increasingly represent a shrinking share of the broader economy. For reference, in the United Kingdom radio has an 80-20 national-to-local advertiser split, and in the U.S. the ratio is approximately reversed. Still, there is much to be positive about the broadly defined medium, especially with the evolution of newer digital services from traditional broadcasters, including Spotify and others that offer podcast advertising, for example.

NEWSPAPERS & MAGAZINES

Many marketers at are least conceptually supportive of print-based media owners. Growing numbers of brands appreciate the importance of this channel as social and cultural consciousness becomes more prevalent in media buying. Concurrently, publishers have diversified their digital offerings to include podcasts, experiential and improved audience matching capabilities that help to ensure viability and long-term growth, especially for publishers with a national or global orientation.

Audiences are therefore robust and available across a much larger spectrum of platforms. However, the broader factors causing decline previously — heightened competition from digital platforms in particular — will continue to weigh on the sector, and many individual publishers that continue to effectively harvest their businesses (i.e., focusing on drawing cash out rather than investing more in) will constrain results for years to come.

Many individual publishers that continue to effectively harvest their businesses (i.e., focusing on drawing cash out rather than investing more in) will constrain results for years to come.”

U.S. POLITICAL ADVERTISING

Finally, we look to the impact of U.S. political advertising at an industry level, which is increasingly important every year, but has a more massive impact every two years — including in 2022. Our new estimates call for $13 billion in ad revenue associated with political campaigns in 2022, up modestly from $12 billion in 2020, but up significantly from 2018’s $6 billion.

Although we do expect a significant uptick in spending that will be associated with a wide range of contentious issues, the absence of a presidential campaign this year limits the degree to which spending can grow on a two-year basis.

On a four-year basis, heightened polarization and relatively loose campaign financing laws continue to support rapid growth in this activity.

Our new estimates call for $13 billion in ad revenue associated with political campaigns in 2022, up modestly from $12 billion in 2020, but up significantly from 2018’s $6 billion.”

REGIONAL GROWTH TRENDS

Looking at the data for 2022 advertising growth through a regional, country or market lens, we first note that there can be two general causes of changes in expectations. The first is a genuine like-for-like change given similar historical baseline estimates for advertising, and the second is driven by a revised analysis of historical data that informs slightly different expectations into the future. Put differently, a change in expectations can be notable, but we emphasize that changes do not necessarily reflect newly positive or negative views unless specifically called out.

CHINA’S OUTSIZED IMPACT

One of the most significant geographic trends relates to the relative deceleration in China compared to the rest of the world. China, which represented 20% of global advertising last year, is now expected to grow by only 3.3% versus 10.2% in our prior forecast. Deceleration of this scale is driven by real underlying changes in expectations relative to six months ago. With a “dynamic zero COVID-19” strategy, lockdowns were a prominent feature in the Chinese economy during much of the first half of 2022, and the policy limits the extent and speed of economic recovery there.

The country’s GDP targets and economic policies are now focused on promoting consumption, infrastructure investment and growth in smaller cities, which should help drive growth in advertising in those areas as marketers broaden their geographic focus. However, advertising will be curtailed by policies that are restricting activities in real estate and education and are generally attempting to curtail celebrity-focused “fan culture.” Efforts to regulate the largest digital platforms in China are also more generally likely to limit growth.

Changes to our estimates in China alone represent a more than 1% reduction in our global forecasts and explain why the weighted average growth rate for the world excluding China is essentially identical now versus our December forecasts (9.6% on an ex-U.S. political basis, excluding China in our current estimates versus 9.7% previously). The median market is down only slightly with 8.2% growth now compared to 9.1% previously. Of course, we recognize that with inflation expectations up by several percentage points on a global basis relative to six months ago, in real or inflation-adjusted terms current growth forecasts would be considered weaker.

NORTH AMERICA

The largest market globally is still the United States, which represents 39% of the global industry. As defined here — excluding direct mail and directories, which we include in our stand-alone U.S. forecasts because of historical conventions — growth excluding political advertising is forecast to be roughly in line with global averages, up 10.0% now versus 10.8% in December.

We note that political advertising is once again expected to be a significant factor in 2022, with nearly $13 billion in activity expected this year for 4% of total media owner ad revenue (highly concentrated in locally skewed broadcasters, with significant volumes increasingly directed to digital platforms).

Canada is expected to grow at a similar pace relative to the underlying U.S. rate of expansion, with a 9.5% growth expectation this year. This represents an upgrade from December’s 6.5% forecast.

EMEA

Looking at other regions, we now forecast Europe and Central Asia, which represent 20% of global advertising, are collectively set to grow by 8.5% this year, up from 7.8% previously. The U.K., by far the largest component of the region at around 29% of total activity, is expected to grow by a faster-than-average pace for the region with 9.3% growth versus 7.3% previously.

Advertising in the U.K. has become increasingly digital-led, as the country has disproportionately benefitted from many of the same underlying trends that have elevated the U.S. and China in recent years. Over the past five years, total advertising revenue for media owners operating in the U.K. has almost doubled, a much faster rate than the 60% expansion observed in all countries globally. Although it is a much bigger economy relative to the U.K., Germany remains Europe’s second-largest advertising market and is now forecast to grow by a similarly upgraded pace, now at 9.1% for 2022 versus our prior 7.3% expectation.

France is seeing a bigger bump with a new forecast of 11.1%; previously we called for growth of only 5.1% in that country for 2022. By contrast, we now expect Italy to fall by 1.6% compared to our prior 5.0% growth expectation. Spain’s growth forecast is also lower now — at 10.6% — than it was in December when our forecast anticipated 11.7%.

APAC

Within APAC we forecast growth of 5.7% now versus our prior 9.3% estimate, although as China represents 56% of the region, relative weakness in China is a drag on the APAC total. Excluding China, regional growth is now forecast to be 9.0%, compared to 8.1% previously.

Japan, still the world’s third-largest advertising market, is forecast to grow at a faster pace than we previously anticipated, and without the benefit of a broadly inflationary economy (consensus expectations per Refinitiv call for CPI increases of 2.5% this year — low globally, although high by Japanese standards, of course). We now forecast 8.5% growth versus 5.6% previously there.

Expectations in the region’s next largest market, India, are relatively unchanged with 22.1% growth forecast for 2022 as underlying growth there remains strong. There is also significant potential for long-term expansion still in place in India, where the population is broadly similar in size compared to China, but India’s advertising market is less than one-tenth as big.

On current estimates, India is positioned to rise from its position as the world’s tenth-largest market to become the seventh-largest — ahead of Canada, Australia and Brazil — by 2025. Australia is expected to grow more modestly — up 5.8%, down from 6.2% previously — although we note that current levels of inflation are more moderate there than in North America or Europe.

South Korea is expected to grow at a much slower pace, up only 1.0% under current expectations versus 1.8% previously. Growth has been more moderate in South Korea in recent years relative to other advanced economies, arguably because a lack of pandemic-era lockdowns limited the degree to which new digitally-focused businesses with high advertising-to-revenue ratios emerged as they did elsewhere.

LATIN AMERICA

Finally, in Latin America, 2022 growth is forecast to be 11.7% now versus 11.4% previously.

The region’s biggest market, Brazil, which accounts for 53% of Latin America’s total, is forecast to be up 13.3% now compared to 12.0% previously.

Mexico, the second-largest country in the region, is relatively unchanged at 12.1% under current expectations for the year.

CONCLUSION

While the economic future is impossible to predict with any certainty, we believe the underlying conditions for most consumers paint a far less negative picture of the risks of current inflationary pressures than many others think. It should be unsurprising after the extraordinary growth of 2021 that we would see a deceleration in 2022, especially among the largest digital players, and there are still meaningful sources of growth fueling the global advertising industry.

Increasing numbers of new small businesses, coupled with their likely propensity to advertise at higher levels than the business they are replacing, venture-funded “new economy” advertisers seeking growth and Chinese-based marketers advertising abroad are significant sources of growth despite some drag brought on by the (expected) deceleration of e-commerce and interest rate hikes.

As a result, we expect the global advertising industry to continue to grow this year, albeit at a slightly slower clip of 8.4% compared to the 9.7% we forecast in December of 2021. And as it swells, publishers and marketers with global strategies will be at an advantage.

Looking at the competitive environment this year and next, it’s becoming clear that the largest streaming services are expanding their global reach, and major digital publishers and platforms are likely to seek global uniformity of their businesses rather than piecemeal changes related to fragmented national and state-based privacy regulations.

While global scale offers marketers easier access to a larger pool of audiences, there will still be challenges to face. U.S.-based streaming services are entering foreign markets and are positioned to take share from national players.

The limited advertising opportunities within streaming services coupled with the overall decline of linear television viewing means marketers should consider defining and setting new goals for the medium of TV as it may become less able to cost-effectively satisfy reach and frequency-based marketing goals.

Even as individual advertising channels are becoming more digital in nature, diversification remains an important tool in every marketer’s toolbox. Laws are changing, economies are in flux and media are evolving rapidly, but there is still ample room for advertising growth and for adaptable marketers to succeed.

APPENDIX

EXPLAINING OUR HISTORICAL REVISIONS

In this edition of This Year Next Year we have made several significant historical revisions to data — digital advertising data in particular — in many markets around the world. In many other places, our pre-2021 data is mostly unchanged, and only final 2021 data for digital advertising looks significantly different than the forecasts published in December.

The root cause of these changes is the same: Much of the industry has been systemically and perpetually under-estimating the scale and trajectory of digital advertising, including many of that sector’s proponents. In our new data, we have taken significant steps to correct for these issues as best as we possibly can.

Before we explain why we have done so, let’s consider some background on the conventional process of estimating advertising activity in a given medium for a given country.

There are several kinds of entities that typically produce raw data on advertising spending or media owner ad revenue for individual media in individual countries. Those entities generally include:

- Governmental bodies, which can use the force of law to compel disclosures or have an estimation process based on data they have.

- Trade bodies, which may collect actual information from willing participants from within their sectors and pair that data with estimates for others.

- Media monitoring services, which build up data sets based on instances of advertisements at the brand level, and pair those instances with estimates of costs per instance.

- Data that is in one form or another based upon agency billings.

Over time, one of these sources will often become accepted as a “truth” data set, and revisions may be made to ensure consistency with our definitions in This Year Next Year.

For example, media monitoring services often lack much information on actual unit costs of media, and whatever they do estimate attempts to capture spending by marketers rather than revenues from media owners. For another example, something like YouTube might be included in the same line item as television in some markets, but under our current definitions, we aim to capture it in our internet-related line items.

A different approach to producing historical estimates, which we apply wherever it is possible, is to analyze public company financial statements to derive our own proprietary estimates of the size and growth rate of a given medium in a given market.

Many of the world’s largest sellers of advertising provide disclosures of advertising revenues, and from there some adjustments might be necessary to ensure definitional consistency. Although those companies might only occasionally include country-level data as we would ideally like to see it, at least the underlying data is rooted in reality as those companies are legally obliged to provide accurate information however it is defined.

Much of the industry has been systemically and perpetually under-estimating the scale and trajectory of digital advertising, including many of that sector’s proponents.”

As public companies produced their final 2021 data early in 2022, it became evident that Alphabet, Meta and Amazon combined to grow their advertising revenues by approximately 42% in constant currency terms. For Alphabet and Meta (which both provide regional disclosures, albeit with slightly different definitions) we could estimate constant currency ad revenue growth of 37% in the United States, 46% growth in the rest of the Americas, 43% growth in EMEA and 41% growth in APAC (excluding China, where virtually no revenue would be attributed on a user-basis for these two companies). Beyond the three giants, we think Microsoft, Yahoo, Japan’s Z Holdings, Snap, Twitter and Pinterest collectively accounted for around $37 billion of incremental revenue last year and probably grew around 30%.

Together, all nine probably represented around $380 billion in digital ad revenue, with very little overlap because of ad network activity. Adding in two other walled garden publishers that provide no specific disclosures on ad revenues — Apple and Bytedance’s TikTok — we can count at least another $10 billion in global activity outside of China, with likely faster growth than whatever the industry average was. Retail media platforms’ directly sold inventory would also add some activity to this total.

Put together, we can intuitively estimate that pure-play digital advertising revenues outside of China would have amounted to around $400 billion last year, with some extra for other smaller digital platforms around the world. Similarly, we can estimate that global growth for these digital advertising activities should have approached 40%. Unfortunately, if we added up all the numbers produced by conventional underlying sources, we would see lower figures.

We believe the reasons behind such differences relate to the process underlying sources go through when gathering data. In the case of digital advertising, local trade associations — probably the most commonly relied-upon underlying source used in any given market — do not typically get actual data from the world’s largest platforms. Instead, they’re left to make their own estimates based on scarce public information. Some of those underlying sources may get actual revenue from large digital platforms within a given market, but we suspect even the country leads for those platforms may not be fully aware of how much revenue flows into their markets from other parts of the world. This issue has increased in scale over time as self-service platforms and cross-country media buying have become more common.

While we have previously made upward adjustments to underlying figures in many individual markets, we made many more of them during this cycle of estimate revisions given the unusual degree of growth the largest industry players exhibited in 2021. It remains difficult to identify exactly which individual markets will require further historical adjustments, but we expect to make additional changes as new evidence emerges to better support making those historical modifications.

We can countat least another$10 billion in global activity outsideof China, with likely faster growth than whateverthe industryaverage was.”

2022 U.S. MID-YEAR ADVERTISING FORECAST BREAKDOWN

U.S. ECONOMIC BACKDROP

The economic situation in the U.S. mirrors much of what was mentioned above in the global section. Data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) has shown persistent high single-digit increases in consumer prices every month during 2022, now a period with the highest rate of price increases for more than 40 years. In response, the U.S. Federal Reserve has raised and will continue to raise interest rates from historical lows, causing concerns that higher costs of capital will constrain economic activity before prices are under control, leading to fears of a stagflationary recession.

However, as negative as these factors are, like our global outlook, economic conditions are actually not quite as bad as headlines might suggest.

As referenced above, consensus expectations from bank economists continue to call for real economic growth this year and next, likely aided by the factors discussed around consumer savings, wage growth and the resulting passing of costs onto consumers where possible. For the U.S. specifically, according to the BLS, wage gains for low-wage earners who are less likely to have much in the way of savings or assets to fund shortfalls actually rose by 9.3% during the first quarter of 2022, continuing an inflation-beating trend that has broadly occurred over much of the past decade for this group.

Let’s consider what expectations looked like for 2022 if we go back one year when vaccines were being administered and inflation was not yet a significant concern. At that time, consensus expectations for real (inflation-adjusted) gross domestic product (GDP) growth in 2022, according to Refinitiv, amounted to 4.1% with inflation expectations of 2.2%, for better than 6% growth in nominal terms.

Fast forward to the present where expectations for 2022 growth in real terms is 2.8% with inflation expectations exceeding 7%. As a result, nominal growth is implicitly forecast to be around 10% during 2022. As This Year Next Year tracks nominal advertising revenue growth, these nominal figures are the data we are ultimately paying the most attention to and represent the singular economic variable to which one might most appropriately tie advertising growth.

Similarly, expectations for nominal growth in 2023 are higher now than they were last year, although of course, we recognize the weaker expectations for real GDP growth reflect a less desirable outcome than might have been hoped for at this point in 2021.

With these conditions, it should be unsurprising if most marketers would generally continue to increase their budgets for advertising at least in line with revenue growth. This occurs in part because many companies manage these budgets in a relatively mechanical manner, but also because some need to sustain a media presence to justify higher prices. Another rationale for increasing advertising is to avoid loss of share to competitors who, in a growing economy, will almost certainly collectively advertise more in order to capitalize on the growth in consumer spending that is likely to occur.

At the same time, the three key secular drivers of advertising we mentioned in the global section are similarly taking hold in the U.S.

THE IMPACT OF NEW GOVERNMENT POLICIES

Beyond the broad changes in the economy that have generally evolved independently of any one government’s choices, it is important to contemplate the degree to which policies are positioned to impact the media business.

When it comes to digital media platforms, in recent years, American legislators and policymakers have started to take notice. Over the last 24 months, in particular, the U.S. government has made numerous efforts to regulate three of the biggest sellers of advertising by proposing or beginning to implement laws that are intended to constrain the choices those companies make and to generally limit their market power. We see this in terms of how Alphabet’s Google and Meta’s Facebook sell ads and engage with other parts of their ecosystems, how Apple and Alphabet work with app developers or how Amazon works with third-party merchants.

Constraining actions, forcing break-ups or creating conditions where break-ups become more appealing than the status quo via policy is relatively certain. Most importantly for our purposes, while any of these outcomes introduce certain problems or risks for the industry, it seems very unlikely that any of those actions will impact overall advertising growth rates. We generally retain the view that while such changes may impact specifics around where money goes within the ecosystem, we don’t believe they will impact marketer budgets by very much, if at all.

In that spirit, we’ve seen individual American states aim to prevent social media platforms from blocking individual users or specific types of content. If these efforts prove successful, they could have implications for markets around the world if the major global platforms, as all of them except Bytedance are U.S.-based, are more likely to think of their home market’s standards as baselines for everywhere else.

For an illustration of these kinds of efforts, refer to the commentary in the global document on the Texas law HB20, the Florida legislation also targeting large social media companies and the Ohio effort to designate Google as a so-called common carrier.

In the U.S., these cases particularly matter because social networks have long relied on Section 230 of the 1996 Communications Decency Act to allow them to handle user-generated content and filter harmful language. If the above efforts succeed, they could open platforms to litigation if the new laws are not adhered to, should they pass. How the world’s digital media giants might adapt and how marketers would respond to environments that would be decidedly less desirable than they are today remains unclear.

Regulatory efforts aimedat forcing break-ups certainly pose risks for the industry but seem unlikely to impact overall advertising growth rates.”

ADVERTISING INDUSTRY GROWTH

Generally, we hold the view that so long as real (inflation-adjusted) economic growth is positive, inflation should be a positive contributor to advertising growth — if economy-wide inflation runs hotter than we expect this year, so too should our forecasts for advertising because of the general impact inflation has on advertiser budgets.

With all of this in mind, we expect advertising in the U.S. including direct mail and directories to grow by 9.3% in 2022, slightly below our prior 9.8% forecast from December due to modest downward changes in digital advertising to better reflect updated data and commentary from the medium’s largest sellers of advertising.